With the history and context of different regulators covered in last weeks post, let's dive into...

The United States possesses a complex and multifaceted financial regulatory environment designed to protect investors and uphold market integrity. This post reviews key milestones shaping the regulatory framework that governs Registered Investment Advisers (RIAs), Broker-Dealers, and Asset/Mutual Fund Management companies. As we trace the roots of today's system, we also set the stage for an upcoming discussion on existing "books and records" regulations and upcoming regulatory changes, including emerging FINCEN mandates scheduled for implementation in 2026.

It's A Complicated Picture... So Let's Break It Down

The number of regulators and what they oversee has grown over time, and without a clear view of the history with the associated reasoning, it can be easy to get overwhelmed. Our aim in the first part of this series is to go through some of the history to the financial market structures so that the 'story behind the actions' can be understood. There are many aspects to the financial markets in the USA and this post will be focusing on regulatory history as it pertains to Registered Investment Advisors (RIAs), Broker-Dealers and Fund Management Companies.

Early Foundations and the Genesis of Federalism

Federal vs. State Oversight

The foundations of U.S. financial regulation date back to the debates during the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Delegates were divided between the need for a strong national financial system—including a national currency and bank—and preserving state autonomy over financial matters. This fundamental disagreement about the balance of power in financial oversight has been a recurring theme throughout American history and early tension continues to affect how financial oversight is structured today. Politicians from the northern industrial states generally favored federal government involvement, while those from southern and agrarian states often resisted what they perceived as an encroachment on state autonomy and a concentration of financial power in metropolitan centers, particularly Wall Street.

The First and Second Banks of the United States

-

First Bank (1791–1811): Chartered by Congress to support federal finances and credit, it was allowed to expire amid political opposition to centralized control.

-

Second Bank (1816–1836): Similarly, its charter was not renewed due to ongoing debates about the role of federal intervention.

The Era of "Wildcat Banking" and the Need for Reform

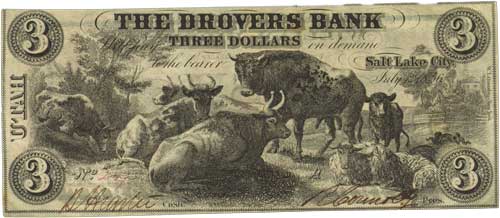

During the 1830s, many states adopted general incorporation and free banking laws. This era, characterized by rampant instability and “wildcat banks” issuing their own currencies, eventually revealed the risks of an unregulated system. The average bank lifespan was about five years, with approximately half of all banks failing, highlighting the systemic vulnerabilities. Indeed, many scholars and economists are drawing parallels between some of the trends in cryptocurrencies with what was observed in financial markets during this time in USA history.

Each bank operating at the time had the ability to generate their own 'notes' aka 'paper money'

This era, characterized by a complete absence of federal control and regulation, ultimately ended with the National Banking Act of 1863 (and subsequent revisions in 1864 and 1865). The National Banking Act aimed to replace the existing state banks with a system of nationally chartered banks, marking a significant step towards federal oversight in the banking sector. The failures of the "free banking" era underscored the inherent dangers of an unregulated financial system and the necessity for a more centralized approach to ensure stability and public trust.

Financial Panics and the Dawn of Centralized Control

In the decades following the Civil War and leading up to World War One, the United States experienced frequent financial panics, including major crises in 1873, 1893, and 1907. These recurring episodes of financial instability prompted legislators at both the federal and state levels to debate reforms to financial regulation.

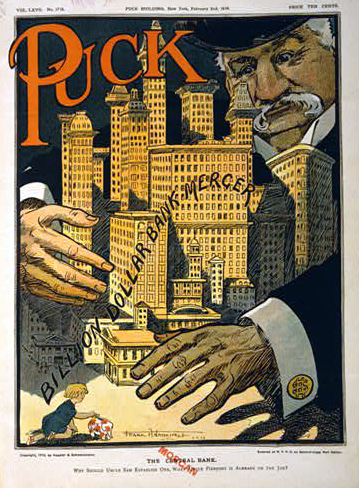

The Panic of 1907, also known as the Knickerbocker Crisis, began with a failed attempt to manipulate the stock of the United Copper Company. The subsequent failure of banks that had financed this manipulation, including the Knickerbocker Trust Company, triggered a rush of depositors demanding their money back, leading to the company's collapse. This panic highlighted the absence of a central bank that could provide a source of assets for struggling financial institutions. In response to this perceived deficiency, Senator Nelson Aldrich introduced legislation in 1910 for the creation of a central bank. Although the initial bill failed, its provisions were incorporated into the Federal Reserve Act of 1913.

While JP Morgan and other banks provided crucial liquidity to avoid a further crisis, many were uncomfortable with the amount of power being wielded by a potential plutocracy

Signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson, this act established the Federal Reserve System ("the Fed") as the central banking system of the United States. The primary objectives of the Federal Reserve Act were to wrest control of the nation's finances from private banks and create a mechanism for a more elastic currency and greater supervision over the banking infrastructure. While the establishment of the Federal Reserve improved the nation's payments system and provided a more flexible currency, the country soon faced another, even more severe financial crisis.

The Great Depression and the New Deal Reforms

The stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing banking panics of the early 1930s plunged the United States into the Great Depression, a worldwide economic crisis. This period of severe economic hardship led to a significant expansion of the federal government's role in regulating the financial sector under President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. The Great Depression thus served as a watershed moment, leading to the creation of the foundational regulatory framework that continues to govern the US financial system today.

President Roosevelt introduced sweeping new federal powers for the Federal Government

Key Legislative Milestones

-

Glass-Steagall Act of 1933: Created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which implemented the regulation of deposit interest rates and, crucially, separated commercial banking from investment banking. This separation aimed to prevent future bank failures by limiting the risk-taking behavior of commercial banks and mitigating conflicts of interest.

-

Securities Act of 1933: Often referred to as the "truth in securities" law, aimed to ensure that investors received financial and other significant information concerning securities being offered for public sale and to prohibit deceit, misrepresentations, and other fraud in the sale of securities. This act mandated the registration of securities with the federal government, requiring companies to disclose essential facts about their business, the securities they were selling, and the risks involved.

-

Securities Exchange Act of 1934: Established the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and solidified the expanding role of the federal government in protecting the investing public by establishing a new administrative agency with broad powers to oversee the securities industry, monitor markets, enforce securities laws, and develop new regulations. The SEC was tasked with ensuring full and fair disclosure of financial information, supervising market practices, and administering credit requirements for securities trading.

Post-New Deal Stability and Deregulatory Wave

The period following the extensive banking reforms of the New Deal, lasting until approximately 1980, was characterized by a relative degree of banking stability and economic expansion. However, by the later part of the 20th century, the heavily regulated commercial banks began to lose market share to less-regulated and more innovative financial institutions. This shift in the competitive landscape led to a significant wave of deregulation throughout the last two decades of the 20th century. The early 1980s, following at least a decade of debate about restructuring the financial services industry, saw a strong movement towards deregulation.

Goals of this time were to improve the competitiveness and efficiency of the USA markets

Landmark Deregulatory Acts

-

Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act (1980): DIDMCA allowed banks greater flexibility to adjust interest rates, spurring increased competition and reducing the reliance on rigid, fixed rate structures. It also broadened access to Federal Reserve facilities by requiring nonmember banks to hold reserves and enhancing monetary control.

-

Garn-St Germain Depository Institutions Act (1982): The act introduced adjustable-rate mortgages and permitted thrifts greater freedom to diversify their asset portfolios, thereby loosening previous regulatory constraints. These measures encouraged innovation and competitiveness among financial institutions by relaxing traditional limits on banking practices.

-

Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (1999): This law repealed key separation requirements of the Glass-Steagall Act, allowing commercial banks, investment banks, and insurance companies to merge and offer bundled services. It also mandated that financial institutions safeguard consumer data by disclosing their privacy policies and information-sharing practices.

2008 Global Financial Crisis and Regulatory Response

During the American housing boom of the mid-2000s, financial institutions significantly increased their marketing of mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) and sophisticated derivative products. This period saw a rise in risky lending practices, particularly in the subprime mortgage market. In 2007, the housing bubble burst, leading to widespread mortgage defaults and a severe contraction of credit. The ensuing financial crisis in 2008 had a global impact, marked by the collapse of major financial institutions and a significant downturn in the global economy.

President Obama signed the Frank-Dodd Act that in many ways, was brought forward as a response to the 2008 Crisis

Introduced Reforms

-

Emergency Economic Stabilization Act (2008): Authorized the use of $700 billion to purchase distressed assets and provide cash to banks thereby stabilizing financial institutions.

-

Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (2010): Introduced stringent regulations on banks and financial institutions with several new regulatory bodies including the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC). It also introduced or codified more stringent regulatory capital requirements for financial companies and granted the FDIC new resolution powers for large financial companies deemed "too big to fail".

Recent Trends and the Evolving Landscape

The U.S. financial regulatory environment is continually adapting to new market developments, technological innovations, and shifting political priorities. Global pressures are driving stricter financial crime enforcement, prompting banks and financial institutions with international operations to reassess their compliance strategies regularly. Notably, presidential elections often signal potential regulatory shifts, as changes in leadership can reshape agency rulemaking and influence priorities around emerging technologies.

Regulation Best Interest (Reg BI) is a prime example of modern regulatory evolution. It imposes a higher standard of care on broker-dealers, requiring them to act in the best interests of retail customers by thoroughly disclosing conflicts of interest and ensuring that their recommendations align with investors’ financial goals and risk tolerance. This enhanced standard goes well beyond traditional suitability guidelines, fostering greater transparency and protection for investors.

Looking ahead, the intensity of regulation for investment management firms is set to increase. RIAs will face new anti-money laundering (AML) and countering the financing of terrorism (CFT) requirements by January 1, 2026, further expanding the regulatory obligations for these entities. Overall, the dynamic nature of U.S. financial regulation demands continuous adaptation to remain both compliant and competitive.

Conclusion

The evolution of U.S. financial regulation—from early federalism debates and the turbulent Wildcat Banking era through New Deal reforms and the deregulatory wave, to the post-2008 reform landscape—reveals a dynamic history of adaptation and reform. This historical perspective not only shapes current oversight for RIAs, broker-dealers, and asset management companies but also frames the challenges ahead in an increasingly complex regulatory environment.

Stay tuned for our next installment, where we will explore the detailed application of books-and-records regulations and the modern compliance challenges facing these financial entities.

.png)